Blog: As Countries Set Ambitious Targets for Electric Vehicle Sales, More International Trade and Domestic Investment Is Needed

In an effort to curb emissions, governments in major vehicle markets are proposing and adopting requirements that electric vehicles (EVs) make up a certain percentage of new vehicle sales in coming years. This week the Government of Canada announced EV sales targets of 60% by 2030 and 100% by 2035 for light-duty vehicles, similar to the goals the United States announced last year of 50% by 2030 and 67% by 2032. Other countries and regions such as China, Japan, and Europe have also made commitments to specific targets.

These targets raise a key question: Can enough electric vehicles be produced in time across the range of countries making these commitments?

Answer: Maybe. There is a great deal of uncertainty, but this is clear: keeping trade open will help, and investing in domestic EV production is critical.

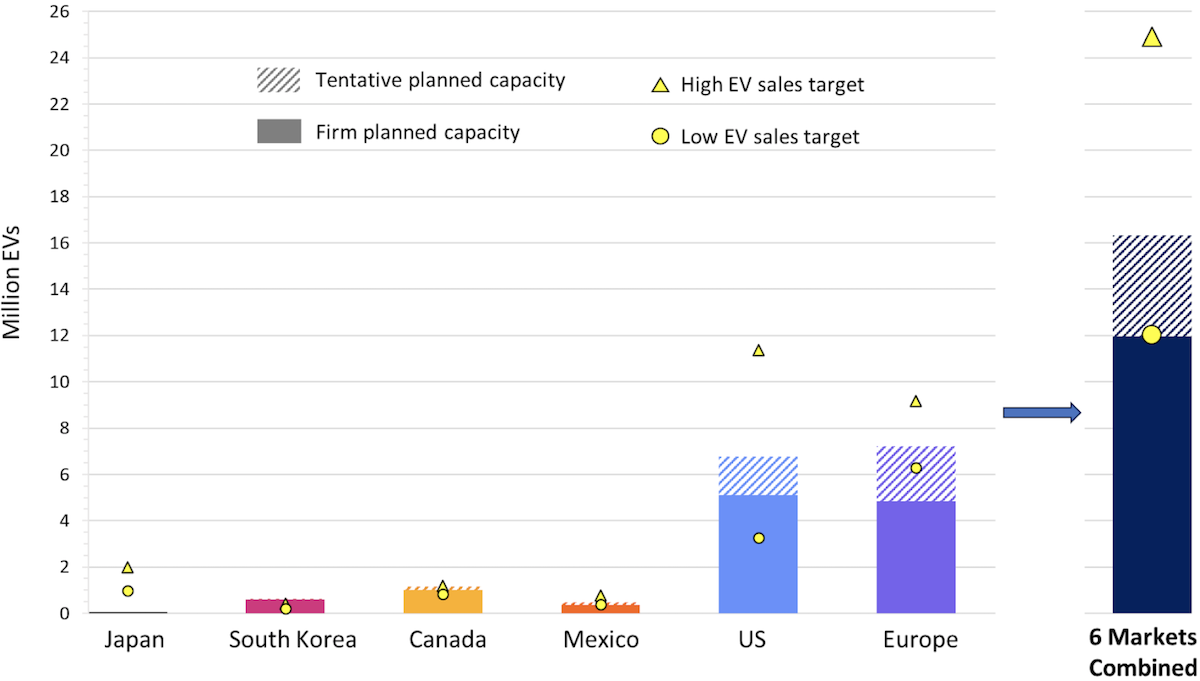

In a recent study, we modeled scenarios in which governments in six electric vehicle markets—the US, Europe, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and South Korea—adopt sales targets requiring EVs to make up a certain percentage of their new vehicle sales by 2030. Depending upon whether these governments adopt higher or lower proposed targets, the markets will need 12 to 25 million new EVs per year by 2030.

The chart below shows the comparisons between higher and lower national EV sales targets, on one hand, and higher and lower company planned EV production capacity, on the other hand. The higher and lower planned production capacities represent “tentative” and “firm” plans and investments, based on our review of related announcements by automakers beginning in 2020.

Comparison of low and high proposed EV sales targets (yellow dots and triangles) with firm and tentative planned production capacity (solid and hatched bars) for 2030.

As shown by the right-hand bar in the chart, if these six governments were to adopt the lower proposed targets, their combined EV production capacity, according to “firm” plans, would be just enough for the required 12 million EV mark. But, if they adopt higher targets (here assumed to be 50% EV sales shares by 2030), their combined production capacity could have a shortfall of 9 to 13 million EVs in that year—which is a third to half of the total number of EVs needed across the countries.

If national shortfalls are relatively small and limited to few of these individual markets, then trade among them could make the combined goals achievable. For example, the US and Europe—the two largest EV markets examined—can achieve their lower sales targets if their planned capacities are pooled. So transatlantic trade may serve as an important approach for reaching combined targets.

On the other hand, with the higher targets, especially combined with lower “firm” production capacities, the shortfalls are too great to be made up only through trade among these countries. In the US-Europe example, their combined annual production shortfall would reach 10.6 million EVs in 2030. This may be addressed with additional automaker investment in each region; if done in line with each region’s needs, the total investment would be $108 billion, which would require an additional $66 billion above the current firm commitment of $42 billion. In this case trade—between these countries and also including additional countries such as China and India—can still play a key role, since it would provide more flexibility regarding where these needed investments can be made.

However, while trade of EVs and their parts can help, trade dynamics are complicated and subject to limitations by regional and national policies and geopolitical matters. These limitations reinforce the need to boost investments in production capacity within each market, though it is unclear that each market will be able to meet 100% of its own demand in the high target scenarios. We believe it is very important to keep trade options as flexible as possible.

Another factor affecting supply is that manufacturers are understandably wary of making large EV production investments in the short-term, because producing the required number of EVs to meet a sales target does not guarantee that consumer demand will follow and protect the companies from financial loss. So attracting the large investments needed is complicated, and policies and incentives that support demand are key. One hopeful example is California, which has an EV sales target of 100% by 2035 and policies supporting demand. In that state, EV sales have skyrocketed from about 7% of new vehicles in 2020 to nearly 27% in 2023.

We do not know yet how targets, demand, or supply growth will play out. Other unknowns not examined or modeled in our study, such as availability of raw materials for batteries and batteries themselves, may also affect production capacity. Right now, the situation looks challenging in the 2030 timeframe. The US and other countries may need to encourage greater investments in EV assembly capacity so this can ramp-up more quickly. More trade may also help, but comes with its own limits and risks.

—

Hong Yang is a PhD candidate in the UC Davis Energy Systems Program.

Lewis Fulton is the director of the Energy Futures Program at ITS-Davis and the former director of the Sustainable Transportation Energy Pathways Program at ITS-Davis.